Should Label of Origin Also Include the Origin of the Feed?

2024.04.21

Christian Sjöland has a background in business, holding a MSc in Business Administation specializing in business development and internationalization. He is also a project manager in the program area Future Food at Axfoundation.

Christian Sjöland’s Sustainability Insights: Many would agree that buying local products is important, but one could argue that it’s especially important in Sweden. At least when Swedes shop for meat, eggs, and milk in the store. Swedes have strong confidence in Swedish agriculture and often boast about its high environmental ambitions and low antibiotic use. Sweden is 83% self-sufficient in pork, 87% in eggs, 76% in chicken, and 73% in milk. Recently, the Swedish government decided that restaurants must label the origin of meat, since many people want to choose Swedish when dining out. But how “Swedish” is Swedish poultry, fish, and pork really? In times when crisis preparedness, supply security, and especially the consequences of environmental changes become more noticeable, perhaps it’s time for a label guaranteeing 100% Swedish feed?

What are the challenges with animal feed?

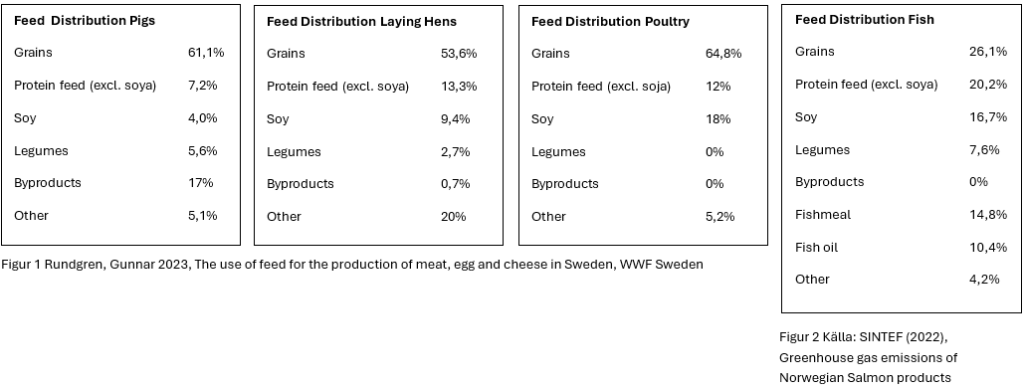

In Swedish animal production, 2.3 million tons of feed grains and 675,000 tons of protein feed (such as soy, fishmeal, rapeseed, and sunflower seeds) are used annually. Approximately 2% of the feed grains and 70% of the protein feed are imported. Adding this up, around 17% of all feed consumed by animals in Sweden is imported, while 83% of the feed comes from domestic production.

Primarily, soy and fishmeal have been identified as the villains in this drama.

That actually sounds pretty good. The major challenge, however, is that protein feed, and especially imported protein feed, has a significant climate impact and poses high environmental risks.

Primarily, soy and fishmeal have been identified as villains in this drama. For instance, a whopping 78% of Swedish ocean fishing goes towards fish feed – a heavy exploitation of marine ecosystems driving them towards collapse. Soy, especially non-European soy, contributes to deforestation by encroaching on sensitive parts of our planet’s arable land, even if certified.

In addition to the fact that the production of these protein feeds contributes to one of the greatest threats to global biodiversity, it’s also challenging to ensure environmental standards are met during production. The dependence on imported protein feeds also creates vulnerability in Sweden’s food supply during heightened crisis preparedness.

Moreover, grain production is almost entirely dependent on input goods: to create animal protein, feed is required, and to create feed, crops are needed, which, in turn, necessitates input goods such as fertilizer, fuel, and pesticides. So even if all feed were produced in Sweden, feed production would still be import-dependent, as Sweden currently imports all its fuel and pesticides.

Around 16-20% of chicken feed consists of imported soy. Photo: Unsplash

Facts about animal feed

- Around 16-20% of chicken feed consists of imported soy.

- Approximately 10% of laying hen feed consists of imported soy.

- About 4% of Swedish pig feed consists of imported soy.

How Does Origin Labeling Work Today?

Some of today’s food labels and certifications require transparency regarding the origin of feed. However, this applies only to a portion of the total feed:

- The Swedish Sigill certification requires that 70% of the feed must be Swedish-produced.

- Swedish KRAV certification stipulates that farms with laying hens, poultry, and pigs must achieve a 50% self-sufficiency rate in feed.

- The voluntary labeling “from Sweden” does not regulate the use of imported feed but solely considers that animal husbandry has taken place in Sweden.

The requirements set by Swedish certifications for protein feed often involve certified soy or sustainably sourced fishmeal.

Blue mussels from the Baltic Sea are one of several raw materials that could be used in the feed of the future. Photo: Ecopelag

A Vision for Future Feed

In the project “The Feed of the Future for Fish, Pigs, Poultry and Laying Hens“, Axfoundation, along with several partners, explores the question: What is sustainable feed? Climate emissions are undoubtedly important, but they are just one aspect of a complex system. Equally important are land use and biodiversity conservation.

Could we, as a civilization, primarily utilize regenerative feed ingredients, that is, organisms that “eat” the substances we want to dispose of? Raw materials with low appeal for human consumption that constitute by-products from green industries? Examples of these include Baltic Sea mussels that reduce eutrophication, mycoprotein that cleans waste water from paper industries, or Black soldier flies that consume food waste.

Could we, as a civilization, primarily utilize regenerative feed ingredients, that is, organisms that “eat” the substances we want to dispose of?

Can we then add nourishing plant crops to the feed, such as legumes that store nitrogen as they grow, or hemp that effectively sequesters carbon? As a last resort, if these ingredients together do not form a complete feed, virgin consumable crops, like wheat—currently the bulk of feed—can be added.

We must produce food in such a way and in such quantities that it aligns with the nutrient flows available on Earth.

What Would the Effects of this Approach Be?

This system would inevitably impose certain limitations on the number of animals that can be raised on such feed. However, that is precisely the point. Our biosphere has limited resources. We must produce food in such a way and in such quantities that it aligns with the nutrient flows available on Earth. By addressing the gaps in feed production now, we can contribute to gradually improving biodiversity, agriculture, and self-sufficiency tomorrow.

Could the eggs of the future be produced using a feed that contributes to cleaning the seas and strengthening crisis preparedness? Photo: iStock

What Would the Effects of such a Feed Be?

- Demand for legumes and other nourishing protein crops, such as hemp, would increase, encouraging more farmers to incorporate these crops into their crop rotation and reducing the need for fertilizers.

- Demand for regenerative protein ingredients, such as mycoprotein, blue mussel meal, and meal made of American soldier flies, would rise. This would also enhance circularity in agriculture. Expansion of these industries would lead to lower prices for these raw materials.

- It would increase Sweden’s self-sufficiency rate, thereby reducing Sweden’s vulnerability during increased crisis preparedness.

So, is there a need for a label that requires entirely Swedish feed? What’s important is that Sweden increases the proportion of regenerative and nourishing ingredients in feed while reducing the proportion of resource-depleting ingredients. Labels can be crucial tools in achieving this, and a label that raises the requirements for Swedish protein feed will make a significant difference along the way.

It’s worth digging deeper into this. And perhaps even challenge it. Who will be the first to introduce a label for entirely Swedish feed? I know I would like to buy eggs that contribute to cleaning our seas and strengthening Sweden’s crisis preparedness.

/Christian Sjöland, Project Manager Future Food, Axfoundation